by Abu Ahasan

A middle-class senior citizen from a residential area in Dhaka city was “officially” recognized as the second to succumb to a coronavirus death. In a heartrending and thought-provoking Facebook post, his son revealed several codependent incidences that led to the demise of his dad. A private hospital initially recommended the patient for COVID-19 testing. Still, the Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) was reluctant to test him. It was because 1) he was not an immigrant 2) didn’t travel abroad 3) or come in contact with oversees returnees in recent times. The IEDCR authorities assured his family that the coronavirus had not begun to spread at a “community” level in Bangladesh.

Family members of the severely ill patient went to reputed private hospitals, without much success. The first did not have an ICU (intensive care unit) facility; the other was reluctant to admit him. Not to mention, neither had the capacity for COVID-19 testing. Meanwhile, the relatives kept on pursuing the IEDCR to test him for a possible coronavirus infection. The IEDCR eventually agreed, by which time it was too late. While the elderly patient was fighting the illness, the state (IEDCR) was mostly in denial. Since testing positive, the body of the COVID-19 patient became a possession of the state. Members of the deceased’s family were not allowed to bury the dead body. To prevent transmission, coronavirus victims experience life in quarantine and the dying experience their last moments, entirely alone, with no next of kin or ritual. However, dealing with an infected person without the help of professionals and experts, they had already been exposed to possible infection from the coronavirus.

The son of the deceased wrote about his intense feelings of loss, guilt, and agony as he recognized his failure to arrange proper treatment or any funeral for his father. He never thought that he would have to write on social media at such a painful moment in his life. Nevertheless, a distinctively new experience of social stigma forced him to do so. Rumors spread on some online news portals and social media that his brother-in-law, a recent “oversees returnee,” had spread the virus to his father. Hence, his family not only fell victim to a highly contagious virus but was also increasingly became seen as the spreader of the virus, a threat to the life of the “community.” He had to narrate the course of his father’s tragic death in great detail to clarify that his brother-in-law, the perceived vector, the “container and transmitter of diseases,” had not contacted his family or specifically his deceased father in recent times. How do we explain such an end and the stigma that it invokes?

Medical understanding of affliction or conventional theories of racism will not help us to comprehend this situation. We instead need to make visible the advent and operation of a new kind of othering in the biopolitics and necropolitics of the coronavirus. It is a war of securing the life of the population, aka “community,” that requires strategic negligence or elimination of the life of others. Like many other nation-states, the emerging apparatus of testing and quarantine in Bangladesh predominantly targeted “overseas returnees” (probashi) from coronavirus-affected countries. Migration to abroad (bidesh) is a highly aspirational pursuit in Bangladesh. Likewise, probashi (the immigrant), especially of western countries, is a social identity associated with higher social status in Bangladeshi society. As the coronavirus spread to Italy and Europe, the returnees from that part of the world came under a brand new disciplinary and public gaze as the potential “possessor, vector and transmitter of diseases.”

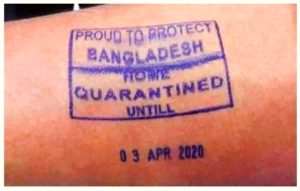

The immigration police recently began stamping returnees on their hands for home quarantine. Police marked the houses of the Italy-returnees with red flags. Journalists and social media ran sensational stories of ignorant, selfish, and unruly returnees, refusing to practice the ideal model of conduct: social distancing and self-quarantine. The misconduct of probashi, rather than the lack of preparedness of the state, increasingly came to dominate the images and imaginations of the coronavirus outbreak. Notably, the first case of death from coronavirus was attributed to “the pathetic self-seeking” behavior of an immigrant. Politicians blamed her for importing a foreign virus from a foreign land and killing her 70-year-old father, portrayed as an “innocent” Bangladeshi citizen. So intense is the marking of “overseas returnees” as the “carrier and transmitter of diseases” these days, the system, for the most part, prevented the elderly, a member of “community,” to express the “truth” that coronavirus had infected them. Were they a victim of the life-threatening coronavirus or the exacerbating bio-politics of coronavirus?

For disease containment and mitigation, it’s largely recognized as necessary to systematically identify the source/transmitter of coronavirus. However, what we have seen in Bangladesh and elsewhere, is an overt focus on specific demographics/geographies as the originator, the carrier, the spreader of the illnesses. Unfortunately, this strategy of containment often takes place at the expense of neglecting the bigger picture of the disease, which involves many other essential factors that can trigger its contamination. Importantly, the governmental technique of identifying “risky” groups/places in the war against the coronavirus activates “biological racism” by establishing a ‘biological-type relationship’ between ‘we’ (community) and ‘they’ (overseas returnees). To defend “community” from sickness, it becomes essential to distinguish the pathological from the normal. While “traditional racism” usually operates through clear markers of supposed racial or ethnic identity, “biological racism” doesn’t target any fixed characters. Based on a specific formulation of war against “biological threat” on the grounds that “society must be defended,” new social groups and identities can be racialized. For example, the sudden transformation of the probashi (oversees returnees, the immigrant) from a signifier of prestige to pollution. The vilification, segregation, expulsion, and surveillance of overseas returnees through a tight grid of disciplinary coercion became a perceived necessity for the survival of the population of the Bangladeshi nation-state.

Biological and traditional racisms are two separate notions for Foucault, but they can also be mutually constructive, such as the discourses that attempt to racialize coronavirus as a Chinese disease. From the very beginning of the outbreak, several Chinese, Russian, and Iranian media outlets portrayed the coronavirus as a biological weapon. For the conservatives in the US, the sufferings of the Chinese became a source of pleasure or schadenfreude; the Malicious enjoyment derived from observing someone else’s misfortune.

There is a long history of the use of epidemics as a metaphor for moral decay, corruption, and evil. Everything was played against China in the geopolitics of coronavirus. The Coronavirus outbreak was associated with primitive and dirty Chinese culture, on the one hand, Chines authoritarianism, on the other. Of course, President Trump, the most excellent troll, took the lead in vilifying the Chinese, but the liberals were also not-so-innocent bystanders. Several articles in the New York Times and the Washington Post predicted the fall of the repressive communist regime due to the corona outbreak. Much energy has been spent in racializing, or Othering Corona; the West perhaps thought that the coronavirus was no match for its excellent, modern, and hygienic way of life. The politicians and scientists surely underestimated the threat of COVID-19.

The World Health Oranisation (WHO) urged countries to “test, test, test.” Massively expanding testing and contact mapping has been regarded as a key in managing the coronavirus outbreak in, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea. However, a large number of governments, significantly the UK and the American governments still limit testing for some specific groups of people and identities. Why is this the case? Is it to do with the lack of resources? When it’s about purchasing military gears or spending for wars, these countries do not seem to face the same economic constraints. I believe it is to do with the number game of coronavirus-related deaths. Through targeting specific sections of the population, rather than the mass, the state can claim its higher rate of success in the war against epidemic based on the lower number of corona deaths. If the US’s coronavirus death toll stays somehow below that of China, Trump can campaign on how great is America. Secondly, through targeting specific groups of people and problematizing their travel histories, behaviors, or places of dwelling, the state can successfully absolve its responsibility to individual citizens, not only of getting infected but also for infecting others. Third, biological racism works to paper over the ongoing structural violence through which modern nation-states govern and regulate their subjects. What is more expedient than generating tremendous communal rages among a section of the population against the other, to obscure the workings of structural violence and modern techniques of marshaling power? The association of coronavirus with “Italy-returnees” and as a “Chinese virus” in different political contexts and cultures, speaks of a similar kind of politics of saving lives that operates through activating a new type of othering, racism and xenophobia.

Abu Ahasan: Anthropologist, PhD candidate of Radboud University, the Netherlands